Simon Jenkins

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 15 May 2012 20.30 BST

Comments (26)

A looming black cloud is hurtling forwards over the European horizon. It is called economic nemesis, driven to a fury by a quarter century of the naivety and greed of most of the continent's rulers. In Berlin and Brussels this week the high priests and wizards of euro-finance gazed at the cloud in horror, muttering imprecations: it was "unacceptable … unthinkable … unmentionable". The cloud took no notice and raced on.

Newspaper financial pages nowadays read like satirical spoofs. No one has a clue what is happening so analysts play with words. Would a Greek exit from the euro be a catastrophe or a calamity, or is that what happens without an exit? Is unimaginable worse than abhorrent, is contagion worse than wildfire, is apocalypse worse than Armageddon?

Markets indulge in no such fantasies. Money talks straight. Computers are already being fed "Grexit" algorithms, and modelling a disintegrated euro. Default swaps are in place. Spanish and Italian debts are being devalued de facto through soaring yields. Politicians panic, but money merely adjusts.

Meanwhile, everyone waits. Even as the currency-shackles around Europe's economy buckle and snap, those supposedly managing it are in denial. It is three years since currency stabilisation was supposedly created, and two years since EU finance ministers pledged "determined and co-ordinated action" to keep Greece in the eurozone. The ministers met again on Monday to moan over their spells and to stick pins in Germany for its meanness. They were unable to grasp the decision required of them, whether to engineer an orderly Greek exit or go beyond that and reorder the euro to create a more economically sensible inner currency. They lacked the necessary political legitimacy. The eurozone is a state without a government.

A weakness of financial regulators is that they must lie. Central bankers and treasuries must swear they mean no devaluation or default until they suddenly do mean it. Each time they lie, they damage their credit for next time. However, even as they lie, they have to be trusted to control events behind the scenes.

At present there is no such trust. It has been clear for years that Greece's political economy cannot manage the cost of euro membership. Debts and subsidies cannot cover its bills any longer. It cannot indefinitely fail to repay money that it should never have borrowed and banks should never have lent. Greeks would become the indentured slaves of Europe in perpetuity. A healthy economy needs some concept of bankruptcy. The message from Greece's democracy this week is to default and take the consequences.

These days only fools voluntarily leave money in Greek banks. An estimated £28bn in euro notes is said to be hidden in Greek mattresses, awaiting release into the economy via a devalued currency. There will be no recovery until this happens. The bullet must be bitten. Banks must go on holiday and come under state control, while debts are redenominated in drachmas. Lenders, savers and importers will take a mighty haircut. Many of the wrong people will suffer. But that is what happens when a country lives on tick.

Only then can this nightmare begin to end. Only with the decks cleared of debt can Greece, like Iceland and Argentina before it, start rebuilding its economy at a realistic rate of exchange. One thing only is certain. A year on, Greece will be on the mend and everyone will wonder why exit took so long, and why anyone believed the fools who said it would be an inconceivable calamity.

The delay in acknowledging this reality is the true calamity. Already the bears are gathering round Spain and Italy, not because their economies are like the Greek one but because markets can read election results as well as they can read riots. The austerities required to bring all the eurozone economies into cost equilibrium with Germany are breaking the back of democracy, and it is Greece that is distracting attention from remedies.

Voters everywhere are punishing governments for repressing demand. What cannot be raised in taxes is borrowed, sending sovereign debt back into the stratosphere. For three years finance ministers have gone cap in hand to Germany, pleading for various forms of bailout. The recent election in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia indicates beyond doubt that such bailing out will not continue.

To its besotted acolytes, the euro was to be the final icing on the cake of political union. It was an exquisitely crafted currency that would enable German efficiency to permeate the continent and usher in a dawn of prosperity and contentment. Sceptics said it would merely enable Germany to swamp lesser economies and wipe their exports from the map.

For a while, Germany knew it was on to a good thing and cross-subsidised (and lent) to cover the gap, much as the British Treasury sustains the UK's poorer regions. But a continent is not a nation. It has diverse loyalties and obligations. Sooner or later the subsidies and the lending would stop. That day is now. The sceptics were right.

If Europe's finance ministers contrived a Greek exit, they would at least have a marginally more plausible euro than now. They could hurl more money at the firewalls round Spanish and Italian debt. They could prop up banks by printing euros. Given the present demand famine and resulting unemployment, this would hardly be inflationary. Contagion might be stemmed and some disciplines sustained on backsliding economies.

This would work only for a while. The sort of fiscal union dreamed of by Germany and its allies in Brussels would soon be rejected by Spanish voters, and eventually by Portuguese, Irish and French ones. Every few years there would be another Greece, and another punishing, debilitating combat between Europe's rulers and market reality. These are wars that markets always win. Why keep fighting them?

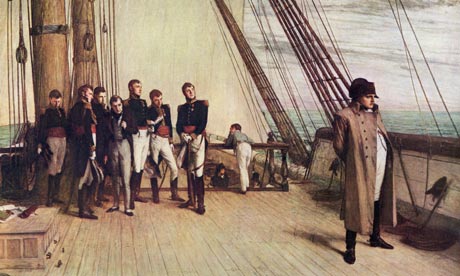

The peoples of Europe are made of crooked timber. They have always fought back against hubristic rulers seeking undue authority over their affairs. While the old Common Market knew its limitations, the euro was a step too far. It required a degree of union that Europe has never tolerated, from the Holy Roman Empire through Napoleon to the Third Reich. It always ends in tears. Kipling remarked after one such conflict: "We have had no end of a lesson; it will do us no end of good." Today's lesson has yet to be learned.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου