ΠΗΓΗ: GUARDIAN

του Μ. Weisbrot

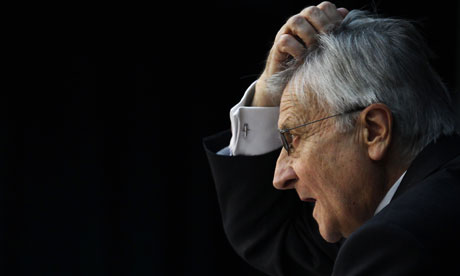

Jean-Claude Trichet, president of the European Central Bank, answers reporters' questions at his monthly news conference at the ECB headquarters in Frankfurt. The ECB is mandated only to control inflation, not unemployment. Photograph: Kai Pfaffenbach/Reuters

The euro is crashing to record lows against the Swiss franc, and interest rates on Italian and Spanish bonds have hit record highs. This latest episode in the eurozone crisis is a result of fears that the contagion is now hitting Italy. With a $2tn economy and $2.45tn in debt, Italy is too big to fail and the European authorities are worried.

Although there is currently little basis for the concern that Italy's interest rates could rise high enough to put its solvency in jeopardy, financial markets are acting irrationally and elevating both the fear and the prospects of a self-fulfilling prophesy. The fact that the European authorities cannot even agree on how to handle the debt of Greece – an economy less than one sixth the size of Italy – does not inspire confidence in their capacity to manage a bigger crisis.

The weaker eurozone economies – Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Spain– are already facing the prospect of years of economic punishment, including extremely high levels of unemployment (16%, 12%, 14% and 21%, respectively). Since the point of all this self-inflicted misery is to save the euro, it is worth asking whether the euro is worth saving. And it is worth asking this question from the point of view of the majority of Europeans who work for a living – that is, from a progressive point of view.

It is often argued that the monetary union, which now includes 17 countries, must be maintained for the sake of the European project. This includes such worthy ideals as European solidarity, building common standards for human rights and social inclusion, keeping rightwing nationalism in check and, of course, the economic and political integration that underlies such progress.

But this confuses the monetary union, or eurozone, with the European Union itself.

Denmark, Sweden and the UK, for example, are part of the EU but not part of the monetary union. There is no reason that the European project cannot proceed, and the EU prosper, without the euro.

And there are good reasons to hope that this may happen. The problem is that the monetary union, unlike the EU itself, is an unambiguously rightwing project. If this has not been clear from its inception, it should be painfully clear now, as the weaker eurozone economies are being subjected to punishment that had previously been reserved for low- and middle-income countries caught in the grip of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and its G7 governors. Instead of trying to get out of recession through fiscal and/or monetary stimulus, as most of the world's governments did in 2009, these governments are being forced to do the opposite, at enormous social cost.

Insults have been added to the injury: the privatisations in Greece or "labour market reform" in Spain; the regressive effects of the measures taken on the distribution of income and wealth; and the shrinking and weakening of the welfare state, while banks are bailed out at taxpayer expense – all this advertises the clear rightwing agenda of the European authorities, as well as their attempt to take advantage of the crisis to institute rightwing political changes.

The rightwing nature of the monetary union had been institutionalised from the beginning. The rules limiting public debt to 60% of GDP and annual budget deficits to 3% of GDP, while violated in practice, are unnecessarily restrictive in times of recession and high unemployment. The European Central Bank's mandate to care only about inflation, and not at all about employment, is another ugly indicator. The US Federal Reserve, for example, is a conservative institution but it is, at least, required by law to concern itself with employment as well as inflation.

And the Fed – for all its incompetence in failing to recognise an $8tn housing bubble that crashed the US economy – has proved to be flexible in the face of recession and a weak recovery, creating more than $2tn as part of an expansionary monetary policy. By comparison, the extremists running the European Central Bank have been raising interest rates since April, despite depression-level unemployment in the weaker eurozone economies.

Some economists and political observers argue that the eurozone needs a fiscal union, with greater co-ordination of budgetary policies, in order to make it work. But rightwing fiscal policy is counter-productive, as we are witnessing, even if it were better co-ordinated. Other economists –including this one – have argued that the large differences in productivity among the member economies present serious difficulties for a monetary union. But even if these problems could be overcome, the eurozone would not be worth the effort if it is a rightwing project.

European economic integration prior to the eurozone was of a different nature. Unlike the "race-to-the-bottom" approach of the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) – which displaced hundreds of thousands of Mexican farmers while contributing to reduced wages and manufacturing employment in the US and Canada – the European Union made some efforts to pull the lower-income economies upward and protect the vulnerable. But the European authorities have proved to be ruthless in their monetary union.

The idea that the euro must be saved for the sake of European solidarity also plays on an oversimplified notion of the resistance that taxpayers in countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Finland have demonstrated to "bailing out" Greece. While it is undeniable that some of this resistance is based on nationalist prejudice – often inflamed by the mass media – that is not the whole story. Many Europeans don't like to pay the bill for bailing out European banks that made bad loans. And the EU authorities are not "helping" Greece, any more than the US and Nato are "helping" Afghanistan – to take a somewhat analogous debate where those who oppose destructive policies are labeled "backward" and "isolationist".

It appears that much of the European left does not understand the rightwing nature of the institutions, authorities and especially macroeconomic policies, which they are facing in the eurozone. This is part of a more general problem with the public misunderstanding of macroeconomic policy worldwide, which has allowed rightwing central banks to implement destructive policies, sometimes even under leftwing governments. These misunderstandings, along with the lack of democratic input, might help explain the paradox that Europe currently has more rightwing macroeconomic policies than the United States, despite having much stronger labour unions and other institutional bases for more progressive economic policy.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου